All of the excitement over drones lately has made me wonder how more widespread use of drones will affect agriculture. We got a preview of the issue last year, when one Congressman falsely accused the EPA of using military drones to spy on farmers. It is true the EPA uses aerial surveillance to look for water quality violations, but as far as I am aware such activities involve old-school tactics–people, Cessnas, and cameras. Still, farmers looking into the future might wonder, could the EPA (or other government agency) use drones to monitor farms?

All of the excitement over drones lately has made me wonder how more widespread use of drones will affect agriculture. We got a preview of the issue last year, when one Congressman falsely accused the EPA of using military drones to spy on farmers. It is true the EPA uses aerial surveillance to look for water quality violations, but as far as I am aware such activities involve old-school tactics–people, Cessnas, and cameras. Still, farmers looking into the future might wonder, could the EPA (or other government agency) use drones to monitor farms?

Aerial surveillance by government agencies is not a new issue. In Dow Chemical Co. v. U.S., Dow challenged the EPA’s authority to conduct aerial surveillance under the Clean Air Act of one of its factories, after it learned that the EPA had flown over at 1,200 feet to photograph interior portions of the plant. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the use of aerial photography was within EPA’s statutory authority, because the Clean Air Act provided that the EPA has a “right of entry to, upon, or through any premises.” In addition, the Court held that the EPA needs no explicit statutory provision to employ methods of observation commonly available to the public.

The test of whether aerial surveillance goes too far and violates one’s right to privacy under the Fourth Amendment is two-fold: First, a person must have exhibited an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy in the property searched; and second, the expectation must be one that society recognizes as “reasonable.” Katz v. U.S., 389 U.S. 347, 361 (1967). If both elements are present, the government can still search the premises, but it must first obtain a warrant. (I have not read anywhere that the EPA obtains warrants before conducting aerial flyovers).

In deciding the Dow case, the Supreme Court distinguished searches between the “curtilage” of one’s home and the “open fields” nearby. “Curtilage” is the “area immediately surrounding a private house.” People have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their home and its curtilage. On the contrary, the Fourth Amendment does not protect the privacy of individuals in areas “out of doors in fields, except in the area immediately surrounding the home.” The Court ultimately found that the Dow factory was an industrial complex, more like an open field than the curtilage of one’s private residence. The EPA’s aerial surveillance was constitutionally allowed.

This does not mean that our courts would approve of the EPA’s use of drones to survey the farms of the entire Midwest, because many farms often include residential homes near farmland, feedlots, manure lagoons, and other areas government agencies might want to see. It is difficult to photograph the open field without also photographing the curtilage of the farmer’s home. That makes aerial surveillance of farming, different than the surveillance in Dow.

Courts will ultimately have to decide how extensively drones can be used monitor agricultural production. One thing is certain—that day is coming.

Todd Janzen grew up on a Kansas farm and now practices law with Plews Shadley Racher & Braun LLP, which has offices in Indianapolis and South Bend. He also serves as General Counsel to the Indiana Dairy Producers and writes regularly about agricultural law topics on his blog: JanzenAgLaw.com. This article is provided for informational purposes only. Readers should consult legal counsel for advice applicable to specific circumstances.

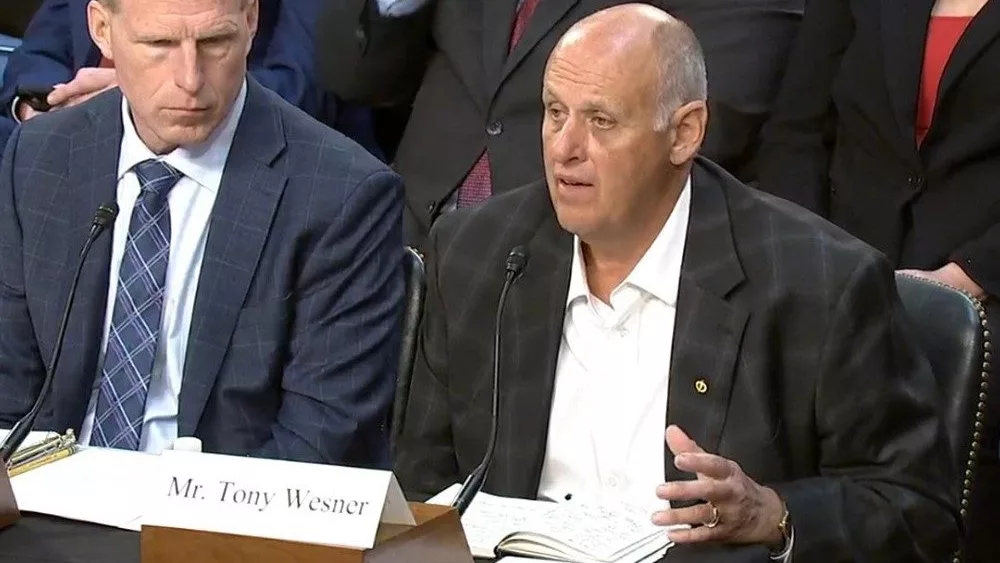

Submitted by: Todd J. Janzen, Plews Shadley Racher & Braun LLP