The strange black circles began appearing on corn leaves in Indiana’s Cass and Carroll counties in 2015. It looked almost as if someone had dipped a brush in black paint and flicked it on the corn. Farmers had never seen anything quite like it, but it gave them a bad feeling.

Researchers at the Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Lab (PPDL) soon identified the problem: tar spot. The disease, caused by a fungus, was well known in Mexico, Central and South America, where it had damaged corn for over a century. But until 2015, it had never been seen in the United States. Now it was here – and it was spreading.

“It can be a pretty devastating disease in terms of corn,” says Daniel Quinn, Purdue’s Extension Corn Specialist. “It can cause significant yield reductions if you don’t manage it properly.”

Since tar spot’s arrival in this country, Purdue researchers have been on the front lines of the fight against the disease. They’re developing new ways of tracking and treating the disease, an effort which reaches across disciplines and national borders.

Know Your Enemy

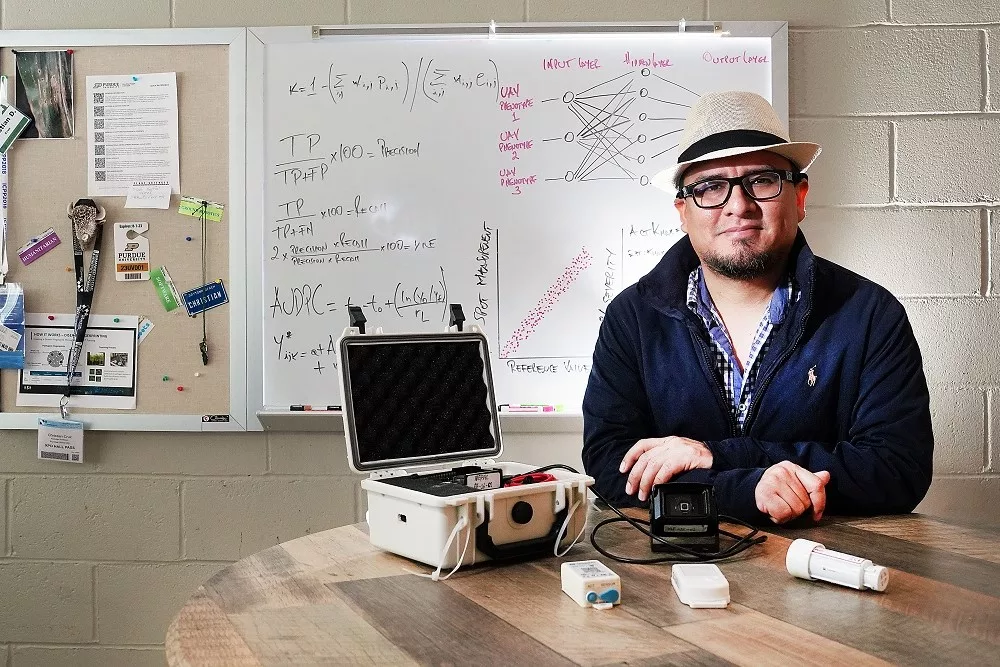

“If you don’t know your enemy, it’s hard to combat the threat,” says Christian Cruz, an assistant professor in the Botany and Plant Pathology Department.

One of the biggest unknowns about corn tar spot is how it got here—understanding how plant pathogens spread involves thinking multidimensionally across disciplines. You need to understand botany, of course, but also things like global trade, international relations, weather patterns and more.

To illustrate, Cruz uses the example of wheat blast, another plant disease caused by a fungus. Since its discovery in Brazil in 1985, wheat blast had only been found in the Americas (though not in the U.S.). But in 2016, it suddenly appeared in Bangladesh and in 2018 in Zambia. Why?

The answer appears to reach back to2014 when Russia invaded and annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula. Suddenly, the region’s massive wheat crop was difficult or impossible to export.

“Countries were desperately looking for sources of wheat,” Cruz says “Brazil was not a major exporter of wheat, but that year it became one. Before shipping, grain might have gotten infected at the farm, and blast infections are sometimes hard to spot. Some of that might have ended up in Bangladesh.”

Researchers are still unsure how tar spot got to the Midwest – it’s now spread from Indiana and Illinois to more than a dozen states across the Midwest, Eastern seaboard and South. But now that it’s here, they need to be able to spot outbreaks quickly. To this end, Cruz and his collaborators, both in the U.S. and abroad, are using a variety of data-collection technologies.

“Drones, robotic platforms, IoT devices, weather sensors, people doing visual assessments or using cell phones to collect imagery,” Cruz lists.

Cruz and his team have been looking at quantifying disease intensity using multispectral imaging – capturing image data within certain wavelengths. Using Red-Green-Blue (RGB) images of affected leaves also seems promising as a way to distinguish tar spot quickly. These imagining technologies could be used in field trials of new hybrids or new fungicides, “looking” for tar spot among test plots to see which hybrids or fungicides fare best.

Cruz’s lab is also looking at using field sensors with an algorithm to detect and quantify the size and extent of tar spot outbreaks.

“Very recently, we started collaborating with people in engineering – robotics, imaging and sensing technologies, mathematics, artificial intelligence, and Extension; cooperation is vital,” he says.

Ultimately, Cruz hopes to help develop a decision-making framework for growers and researchers. “If you’re an end-user, you’d be interested in the level of tar spot, so you can decide to spray a fungicide or not or recommend a different hybrid or cultivar next year,” he says.

A Disease Pushing the Limits

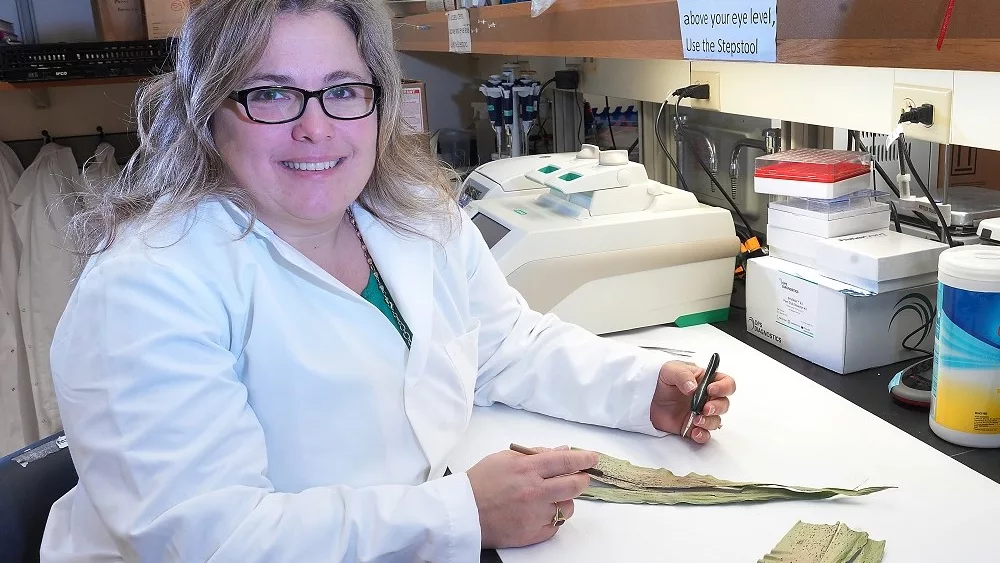

“I started at Purdue in 2018,” says Darcy Telenko, a field crop plant pathologist in the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology. “The first call I got was about a field that turned brown almost a month before it should have.”

During that first year Telenko’ s team documented tar spot in about half the counties in Indiana. Now tar spot of corn has been confirmed in almost all the state’s 92 counties.

“This disease is pushing the limits of our fungicides,” Telenko says.

Telenko and her team are actively looking for solutions: better fungicides, more precise timing for application of fungicides, and more resistant corn.

Currently, when tar spot shows up in early July, farmers will need to stave off disease for two months, until the crop reaches maturity. This may mean two applications of fungicide are necessary, which is expensive and time-consuming. Telenko hopes to figure out the ideal window for application, while working with growers’ logistical constraints, such as when aerial applicators (crop dusters) are available.

Knowing when to apply fungicides means having data about initial infections. So, like Cruz, Telenko is involved in developing better detection and prediction methods. She’s partnered with a team at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, to develop a tar spot application. The app uses weather data to predict when infections are likely to occur in areas with a history of tar spot.

But there are still many unknowns. Scientists understand that tar spot spore infection requires the presence of moisture, but how much and when are still unanswered questions.

“The leaves can’t just be continuously wet,” Telenko says. “There may need to be a fluctuation in moisture or humidity conditions. In Indiana, there are many mornings with a morning dew, that then dries off during the day, and this might be the ideal situation for tar spot spores to gain access.”

Telenko and others are also working on methods for rapidly sampling these spores in the field. Her team currently samples sites regularly, and is helping create tools for evaluating those samples more quickly.

The unpredictability of tar spot year to year is one of the most difficult things for growers, Telenko says. Some years – 2021 was one – bring widespread outbreaks. Other years, the disease only appears in hotspots.

“I have growers from 2018 who, this year, feel like they finally got a handle on this,” she says. “The big problem is, it continues to spread.”

On the Ground Help

When farmers find leaves affected by what looks like tar spot, Quinn encourages them to send it in to Purdue for diagnosis. There are several things that can look like tar spot, he explains, so don’t panic just because you see black speckles on the corn.

“One of the most common mimics is insect poop,” he says. “So we always recommend, if you can scratch it off then it’s not tar spot, but if it’s raised and stays it can be.”

Quinn and his colleagues do regular outreach to educate farmers about tar spot and its management. This includes podcasts, webinars, meetings, public field days, local media spots, and more.

If a grower has a confirmed case of tar spot, Quinn’s advice will depend on the season, the weather, and the extent of the spread.

“If it’s showing up early, we always think about making fungicide applications to corn in mid-July when corn is tasseling,” he says. “That’s a critical period. If you’re seeing it at that point in time, it’s probably going to be a severe year.”

Knowing they cannot eliminate tar spot entirely, all the Purdue researchers hope to greatly reduce its impact on grain production.

“Maybe in 10 years we can say ‘oh that was a big problem, but it’s a minor issue now,’” says Telenko.

Written by Emily Matchar, Purdue Agricultural Communications.